Today I will not draw joy. Today I draw pain. Today I sketch Injustice. Today I paint a prayer. "If I shall die before my run, I pray the Lord my case is won." - Nikkolas Smith

I've had this post in my drafts for the past week. I've been going back and forth on it because talking about police brutality on social media as a black man often feels like screaming into a glass jar. The people around you can see something is wrong by your exasperated gestures and your furrowed brow, but they walk right by, and eventually, after some time, the glass fogs up to the point that from the outside looking in, you can barely make out the outline of a mouth. But violence against black and brown bodies is always an urgent conversation in this country, so please bear with me as I try to find the words.

Having to process the murders of Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor in real-time, while already contending with the disparate outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic on communities of color, especially African Americans, has been crushing. A heaviness on the chest perhaps only matched by the effect of the novel coronavirus on its victims as fluid and mucus fills up their lungs, essentially choking them to death (See Eric Garner: #ICantBreathe). In the past few years, I've taken something away from each subsequent death at the hands of white supremacy. Each life extinguished has become its own morbid marker of the passing of time, and I imagine that years from now, Ahmaud and Breonna will stir up memories of being alive during a global pandemic and still having to deal with living in a racist America. A society where if your life is not blotted out on the street, you might still suffer the same fate in a hospital bed at the hands of a healthcare system saddled with the same structural racism that affects all walks of life as a black person in this country.

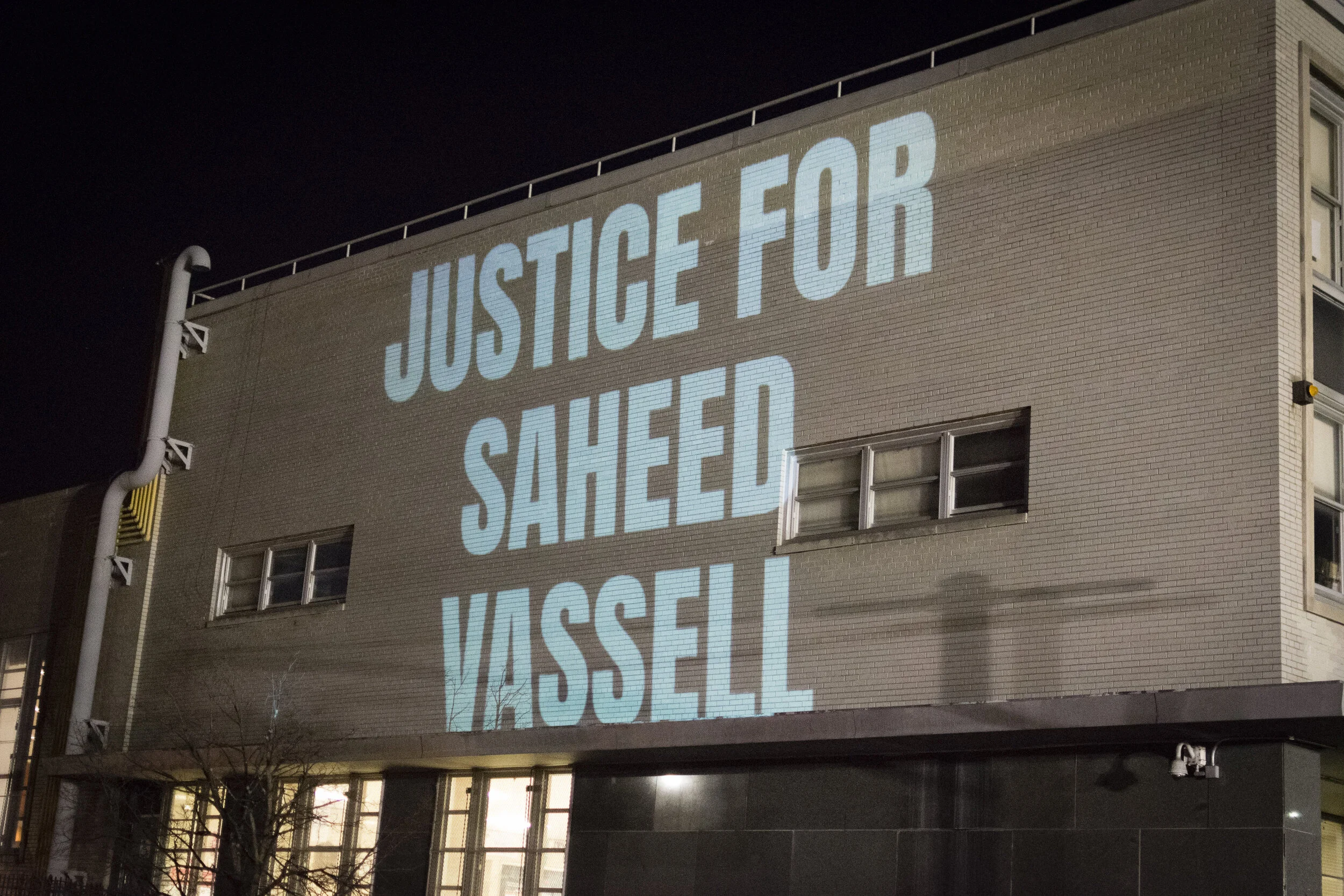

Saheed Vassell was killed by the NYPD on April 4, 2018, at the intersection of Utica Ave & Montgomery Street in Crown Heights. That intersection is only two blocks from my therapist's office and along the route that I walked each Tuesday to my weekly appointment. Saheed's shooting hit me hard because it happened right in my backyard, not in some podunk city in the South or distant metropolis but right in the middle of my world. I couldn't shake the fact that he was killed in broad daylight at a corner that I walked past multiple times each week. I kept thinking to myself, what if I was there that day heading to see my therapist and was struck or even worse killed by a stray bullet? What would the narrative be when they eventually identified my body and called my mother that day? Would the officer who fired the gun that ended my life miss a beat? Would he toss and turn in bed that night wrangling over my death? Or would he just make his way back home after his shift to a nondescript house on a quiet tree-lined street in Staten Island and carry on with his life as if nothing ever happened?

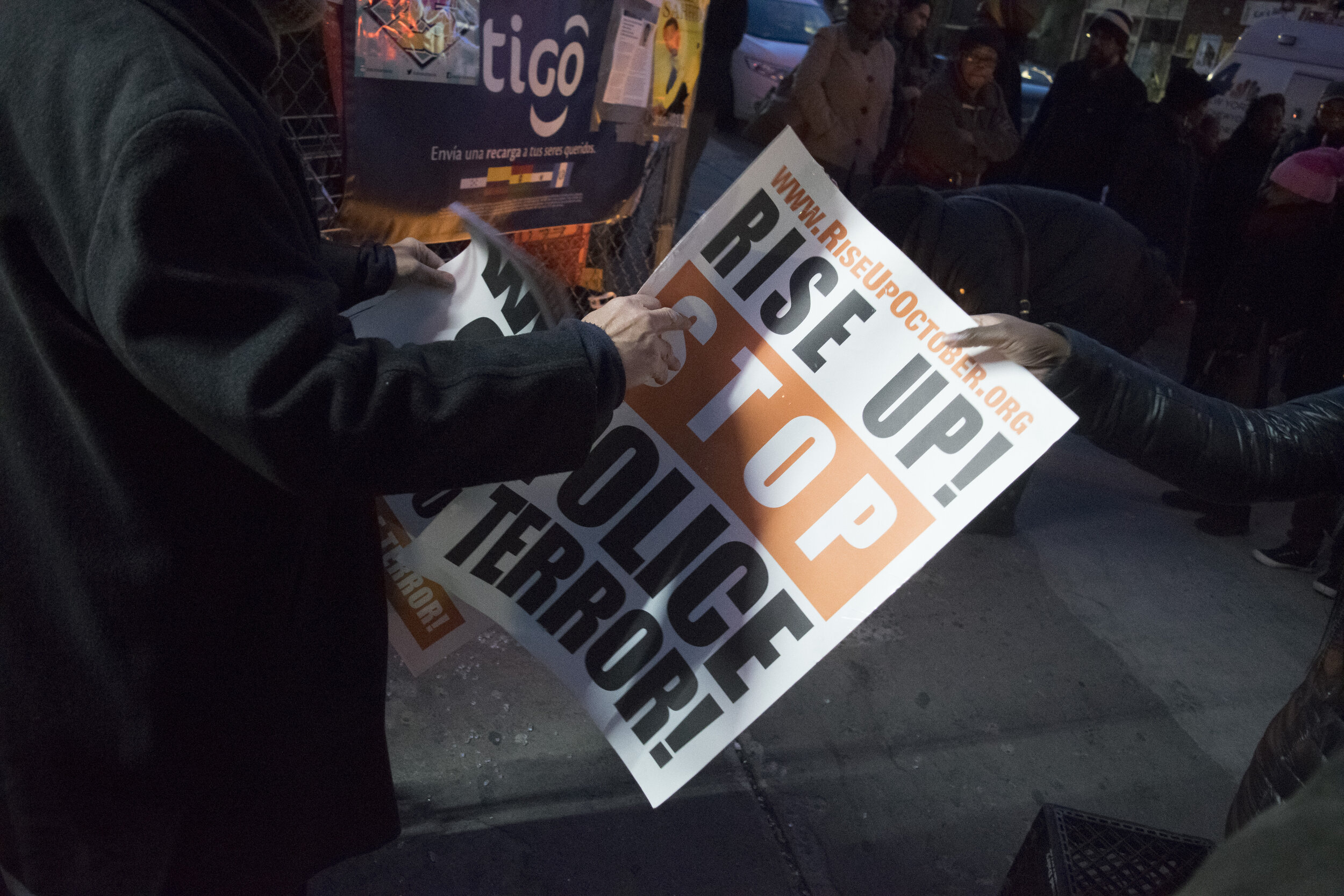

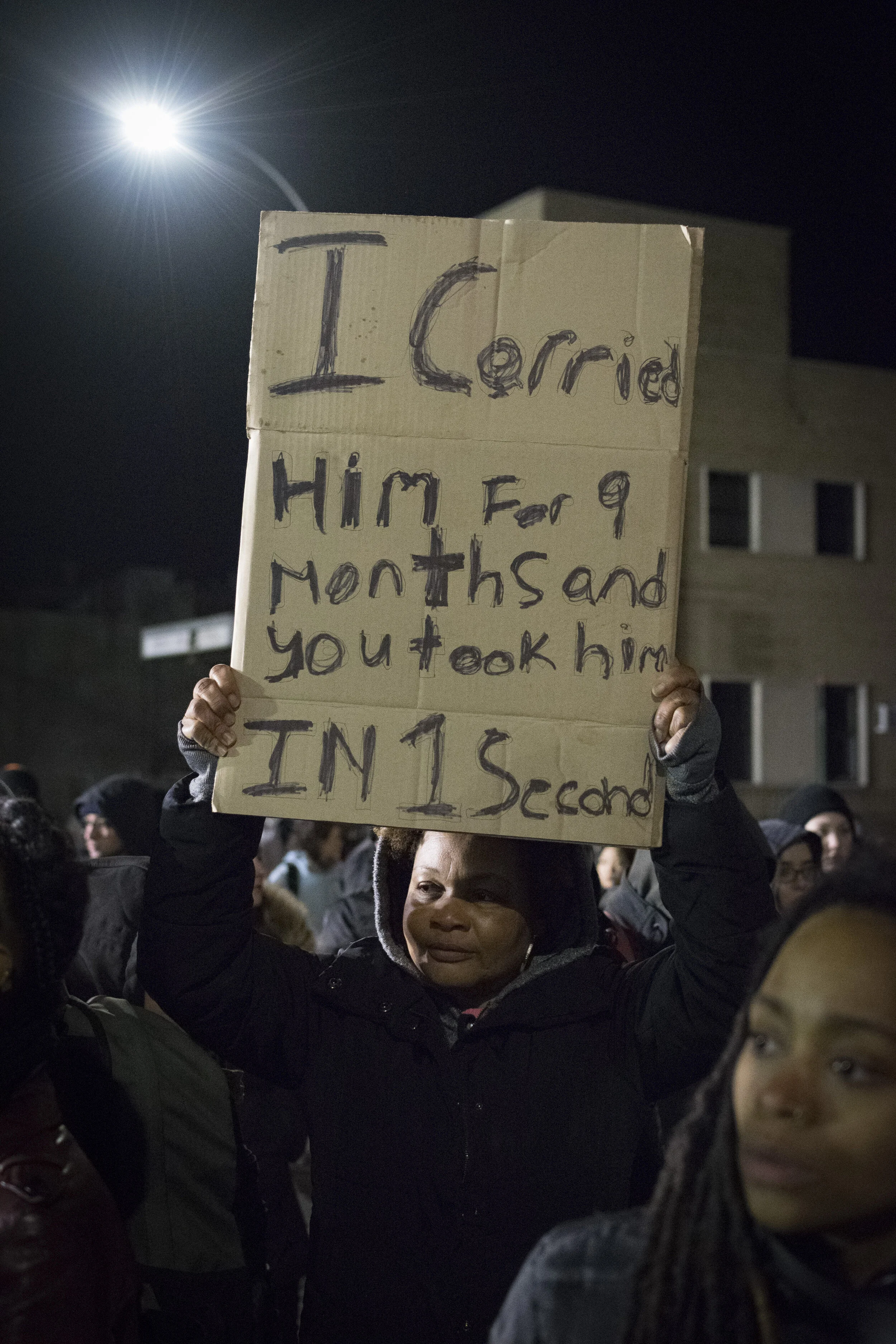

Immediately after Saheed's shooting, the surrounding Crown Heights community organized a vigil to commemorate his life and a protest to seek justice. I wanted to document it as best I could so I made the walk over to Utica Ave & Montgomery Street with my camera and captured everything I could. It's one thing to see the aftermath of these shootings on TV or to read about them in an article, but being there and bearing witness to the pain and anger they inflict on those left to deal with the loss and the trauma is an experience that will forever stick with me. I walked past that same intersection the following week en route to see Edna (my therapist), and you could still see Saheed's blood seeped in the concrete on the sidewalk. Bloodstains are notoriously hard to get rid of; the hemoglobin in blood causes it to clot when exposed to air. This clotting ability helps heal wounds more quickly when you're injured by preventing excessive blood loss. But this same clotting ability also binds it to any surface on which it is spilled, making it difficult to remove from fabric, clothing, and even concrete. Despite the tragedy of his death, I thought it was somewhat poetic that even after repeated attempts, they couldn't wash his blood away. Saheed's death was all I talked about with Edna that week.

Almost exactly a year after Saheed passed, Nipsey Hussle was shot and killed in Los Angeles. I remember hearing the details of his murder and how he was reportedly killed for calling his assailant a snitch, which is the closest thing to a scarlet letter in the hood. My mind and heart were already heavy that week because it was the anniversary of Saheed's death, so the news of Nipsey's death added another layer of complicated thoughts swirling around in my head. I've walked into my therapist's office sad, confused, some days even apathetic … but my session after Nipsey was murdered was my first time ever walking into an appointment visibly angry. I struggled to reconcile with the fact that even someone like Nipsey, who was doing everything in his power to change the narrative of what black boys from the hood could be and what they could aspire to, could lose his life to senseless violence. I remember barking at Edna shortly after sitting down, "What's the fucking point? I do wrong … I die. I do right … I die. I do nothing … I die." Anyone who knows me well knows that even in volatile situations, I almost always keep my composure … until I don't. I fought back tears as I struggled to get her to understand why I was so affected by Nipsey, Saheed, and the countless other black men before them who've lost their lives extrajudicially. While she acknowledged my pain, she struggled to see why I internalized it, and for the first time sitting in her chair, I felt she didn't understand me.

“What’s the fucking point? I do wrong … I die. I do right … I die. I do nothing … I die.”

In retrospect, I feel a little sorry for Edna, despite our shared racial identity I don't think she was fully equipped to deal with the level of anger I was carrying that day. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) does not list racial trauma or race-based stress as a disorder or mental illness. She very well may never have received guidance from a college textbook or sat through a long lecture on how to deal with black boys like me who from a young age continue to be ruthlessly reminded of how little their lives are worth. We've long known the physiological effects of racism on black bodies from the womb to the tomb, but only recently have we begun to interrogate its impact on the psyche and mental health. In the absence of a framework, Edna fell back on the doctrine so many of us receive on simply putting our heads down, putting our blinders up, and minding our business. All too often, whether it's "the talk" from black parents with their sons or white folk assuaging us and other POC with the myth of the model minority, black people are often led to believe that docility and grandstanding will somehow inoculate them from the grips of white supremacy. Time and time again, reality has proven that to be a lie. In the words of Jamil Smith in his recent Rolling Stone piece, "We need a system of laws that honors black humanity, one that doesn't inherently endanger our safety. Convict Arbery's murderers—but also fix the America that killed him."

So just as a recap, being Black in America means:

I can't go jogging (#AhmaudArbery)

I can't relax in the comfort of my own home (#BothamJean & #AtatianaJefferson)

I can't ask for help after being in a car accident (#JonathanFerrell & #RenishaMcBride)

I can't have a cellphone (#StephonClark)

I can't leave a party to get to safety (#JordanEdwards)

I can't play loud music in my car (#JordanDavis)

I can't sell CDs (#AltonSterling)

I can't sleep (#AiyanaJones)

I can't walk from the corner store (#MikeBrown)

I can't play cops and robbers (#TamirRice)

I can't go to church (#Charleston9)

I can't walk home with Skittles (#TrayvonMartin)

I can't hold a hairbrush while leaving my own bachelor party (#SeanBell)

I can't party on New Years (#OscarGrant)

I can't enjoy the benefit of a regular traffic ticket (#SandraBland)

I can't lawfully carry a weapon (#PhilandoCastile)

I can't break down on a public road with car problems (#CoreyJones)

I can't shop at Walmart (#JohnCrawford)

I can't have a disabled vehicle (#TerrenceCrutcher)

I can't read a book in my own car (#KeithScott)

I can't be a 10-year-old walking with my grandfather (#CliffordGlover)

I can't decorate for a party (#ClaudeReese)

I can't ask a cop a question (#RandyEvans)

I can't cash a check in peace (#YvonneSmallwood)

I can't take out my waller (#AmadouDiallo)

I can't run (#WalterScott)

I can't breathe (#EricGarner)

I can't live (#FreddieGray)

I'm tired.

Tired of making hashtags.

Tired of trying to convince you that my black life matters.

Tired of dying.

Tired.

Tired.

Tired.

So very tired.

The following are a handful of images I took during Saheed’s vigil and protest on April 6, 2018 in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. Click on an image to view it at full size.

Extra Credit

To fully appreciate the context of Saheed Vassell’s shooting you need to understand how a gentrifying neighborhood, unaddressed mental health issues, and a lack of representative policing all collided on that fateful day. Check out this MSNBC segment by Joy Reid to learn more. 👇🏿

Resources

“How racism makes us sick” - TED

“Session 134: The Impact of Racial Trauma” - Therapy For Black Girls

"Grief is a direct impact of racism: Eight ways to support yourself” - The Conversation

“Campaign Zero: The comprehensive platform of research-based policy solutions to end police brutality in America” - Campaign Zero